In our leadership development work, whether providing executive coaching to support an individual moving into a more senior position or training leaders across functions within an organization, there is one speed bump we run into nearly every time which needs to be addressed before significant progress can be made. It is the belief that the leader must be The Expert and he/she must have all the answers. The Expert should be directing others, telling them what to do, and solving the problems. Often, this tends to be a cultural issue, organizationally embedded, where hierarchy and silos are more the norm than is risk taking, vulnerability or unbridled creativity. So, what’s so challenging about this belief in expertise? Because if we don’t question this mindset, we may get stuck in one mode, the way we’ve always done it, the way I was taught, the way my boss did it. We don’t develop our own capabilities, and, worse, we may not be developing the talent around us in a positive, productive way.

There are certain predictable behaviors that we find underpinning this limiting belief: the tendency to tell versus ask for input or help, the need to be right, and the inability to delegate effectively.

1. Telling Versus Asking

Take stock: in your organization, what’s the reward for having all the answers? Or does your organization encourage seekers and those who are curious, who ask – hey, what do you think?

Somewhere along the way, as we grew up, went to school, and started our first jobs, we adopted the notion that we must present to the world the image of a person who is expert in some area or function. That we have the answers. We know what to do. And certainly that has to be true in many situations—you were hired because you know how to run a distribution center, or you have expertise building new business, or you are really great at designing new products. That’s why your company and your teammates count on you, right?

But balanced against that role and responsibility is the dynamic of humility which reasonably suggests you don’t actually have all the answers, and, more, that you may not be seeing everything as clearly as you thought. The excuse we hear most of the time is exactly that—time. “I don’t have time to ask questions; the pace here is brutal and we just have to keep moving.” So we go back to barking orders and heads down productivity…but, guess what? That new process that went live last month is not streamlining work production; it’s actually slowing down communication, causing confusion and costing twice as much. If we don’t stop to ask, “what’s working here?” we miss the signs until poor engagement scores and excessive turnover slap us in the face.

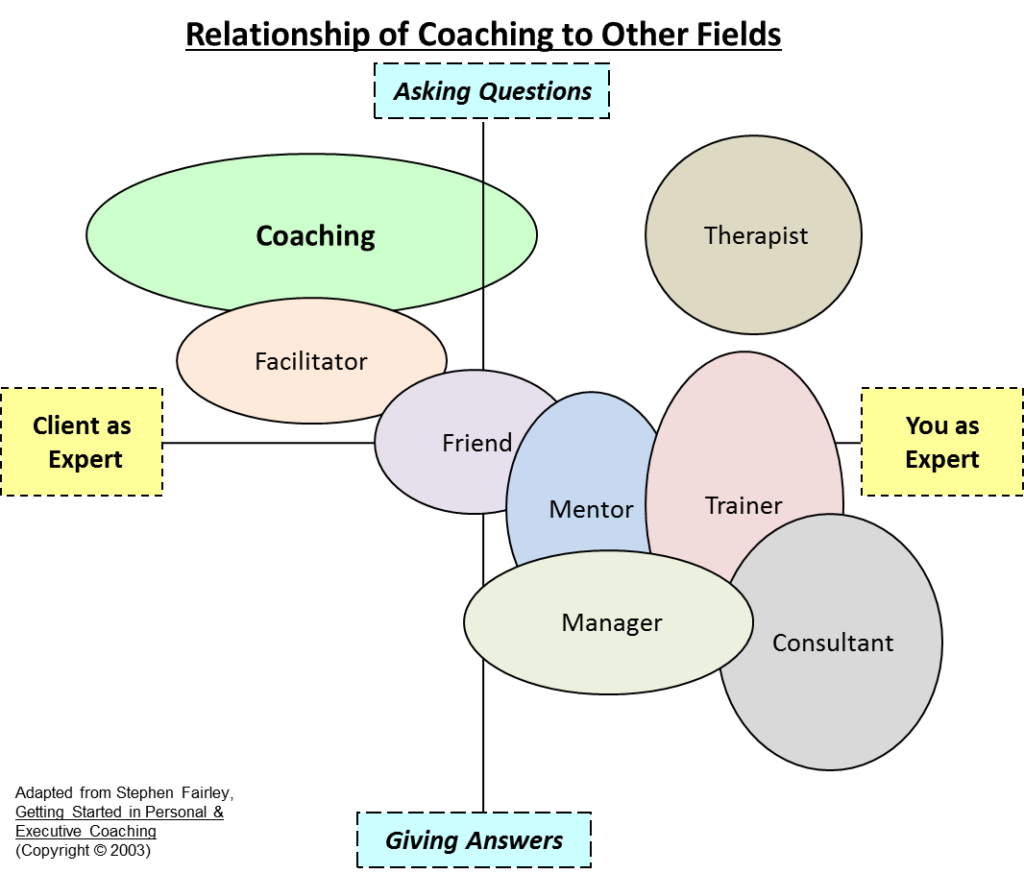

How well do your leaders coach their team members? On the graph below, where do you and your organization fall in terms of encouraging an environment of asking questions, the kind of questions that not only get at information and truth, but questions that open us all up to other possibilities, that encourage participation at all levels within the organization?

2. The Need to be Right – Closed Versus Open

When we think or feel we must always have the answers, there is little room for behaviors that invite others into a potentially creative discussion that could lead to even better answers. We get stuck in a sense of our own right-ness and having to prove it every day. Where did that come from?

I was walking behind two parents and a child of about 5 last week in a park and started to notice a pattern in their discussion. The child would make a comment, “Mommy, look at the loud bicycle”, and the parent would correct her: “That’s actually a motorcycle, not a bike.” Child, spying an ice cream vendor, “Oh, ice cream!!” Parent, “It’s too early in the day for that.”

So what’s wrong with being right? (And who says not having ice cream at 10AM is wrong?) When being right becomes the mantle we hold onto in all situations, we are constantly in the position of proving our points or persuading others (think, politics). We shut down others’ natural curiosity and suggestions. We limit the view we can take on a situation and therefore the possibility for a new resolution.

So, again, on the above graph, where do you and your organization fall in terms of allowing everyone to share in expertise, to offer ideas and suggestions, even when not formally trained in a particular lane? Is your company more likely to support the hierarchy of title, the power of “the boss”, or more inclined to invite a variety of input from many sources?

3. Inability to Delegate Effectively

Consider the difference between providing direction—the vision of where we collectively want to steer the team, department, organization—and literally telling someone what to do to get there. One of the complaints we often hear voiced by senior executives about their direct reports is, “I wish they would just step up more.”

Why don’t they? For starters, lack of clarity about the overarching direction. And against that backdrop, poor delegation skills. What limits effective delegation? In part, we see it as a control issue, particularly for new managers and leaders raised in The Expert tradition. Fear of letting go of control, allowing others to participate in a decision, allowing someone else to be right. There is certainly an art to providing enough direction so that the desired outcome is clear and enough empowerment so that the individual takes the reigns.

Face it, if you are stuck in the lower right hand quadrant of the above graph, you must be absolutely exhausted – always needing to be right, telling everyone what to do, solving all problems. What would it take to shift above the line, to start asking questions that expand the thinking and exploration toward new processes, products or business growth?

Here’s your fieldwork – try these three next time you’re in a conversation. Ask:

1) What do you think?

2) Who else can we talk to about this for ideas and input?

3) What needs to happen next in order for that (desired outcome) to occur and who can handle it?